More Information

Submitted: October 31, 2025 | Accepted: December 23, 2025 | Published: December 24, 2025

Citation: Bodden DHM, Stikkelbroek Y, Creemers D, Rasing SPA, De Caluwe E, Braet C. Screening for Depressive Symptoms in Clinical and Nonclinical Youth: The Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2). Insights Depress Anxiety. 2025; 9(1): 028-039. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ida.1001047

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ida.1001047

Copyright license: © 2025 Bodden DHM, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms; Questionnaire; youth; Psychometric properties; Children and adolescents; Screening; CDI-2 (Children’s Depression Inventory-2)

Screening for Depressive Symptoms in Clinical and Nonclinical Youth: The Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2)

Denise HM Bodden1*, Yvonne Stikkelbroek1, Daan Creemers2,3, Sanne PA Rasing2, Elien De Caluwe4 and Caroline Braet5

1Department of Child and Adolescent Studies, University of Utrecht, PO Box 80.140, 3508 TC, Utrecht, The Netherlands

2GGZ Oost Brabant, PO Box 3, 5427 ZG Boekel, The Netherlands

3Radboud University, BSI, Montessorilaan 3, 6525 HR Nijmegen, The Netherlands

4Developmental Psychology, Tilburg University, Prof. Cobbenhagenlaan 225, mailbox 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands

5Department of Developmental, Personality, and Social Psychology, Ghent University, Henri Dunantlaan, 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

*Address for Correspondence: Denise HM Bodden, Department of Child and Adolescent Studies, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, Email: [email protected]

Objective: This study investigated the utility of the second version of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI-2) as a screening tool to identify children and adolescents aged 8-21 years suffering from depressive symptoms.

Method: Data were collected by combining questionnaire data from multiple clinical and control subsamples in which the CDI-2 child and parent version were administered to clinically depressed children (n = 111), children with other psychiatric disorders (n = 74) and control children (n = 2246) as well as their parents (respectively n = 104, n = 112, n = 2130).

Results: Results showed that the CDI-2 has good psychometric properties in terms of internal consistency, factor structure, parent-child agreement, convergent and divergent validity. However, the factor structure of the parent version was insufficient. The CDI-2 total score of the child version and parent version can differentiate between clinically depressed children, children with other psychiatric disorders, and control children. Further, reliable cut-off scores were established. There were also significant gender and age effects.

Conclusion: The total score of the CDI-2 child and parent version can be used as a screening tool to detect clinically significant depressive symptoms in children and adolescents.

Depressive symptoms in adolescents are a huge societal problem because of their severity, burden of disease, comorbidity, suicide risk, and the high risk to develop depressive and other psychiatric disorders later in life [1-3].

Prevalence rates of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents range from 5.3% (annual prevalence) to 29.2% (point prevalence) [4] and 34% [5]. Despite the high prevalence, depressive disorders are frequently underdiagnosed in children and adolescents (hereafter defined as children) [6,7]. A reason for this underdiagnosis is that the environment is not always aware of the child’s internalising problems. Therefore, a good and reliable screening instrument to detect depressive symptoms from both a child’s perspective and a parent’s perspective seems warranted to identify those with elevated depressive symptoms who are at risk of developing even more severe mental health problems and/or severe consequences, so they can receive appropriate help. A meta-analysis of eight studies showed that 31 children (7-19 years old) have to be screened to successfully treat one depressive child [8]. Screening has been recommended for all children over the age of 12 by the United States Preventive Services Task Force [9] and the American Academy of Pediatrics [10], although no robust evidence for the harms and benefits of screening at this age was found [11]. Besides, a screening instrument can also be used for diagnostics, clinical decision making, early prevention, intervention purposes, and assessing treatment changes.

Different measures have been developed to screen for depressive symptoms. The most commonly used self-rating scale for assessing depression in children is the Children’s Depression Inventory [12,13]. The original CDI was developed as a downward version of the Beck Depression Inventory [14] for adults. The CDI is a 27-item self-report questionnaire to assess the presence and the severity of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents aged 7 to 17 [12]. An advantage of the CDI for participants is that the assessment is not time-consuming (10 to 15 minutes) and easy to read (lowest reading level). For clinicians, the CDI is efficient, inexpensive, and easy to score and interpret. The CDI allows for case identification and assessing a degree of symptom severity, including a suicide item.

Many studies have investigated the psychometric properties of the original CDI. For example, the internal consistency of the CDI is good [15-17]. Research outcomes on the factor structure of the CDI child version vary considerably in the number of factors (1 to 8) and the content of those factors [15,18,19]. A meta-analysis of 24 studies found little evidence for the original five-factor structure of the CDI. While five factors were found, they were completely different content-wise. Therefore, several authors have concluded that one higher-order factor may best fit the structure of the CDI [20].

A study examining the factor structure of both the child and parent versions revealed two different 3-factor structures for the parent and child versions, suggesting that parents’ and children’s reports focus on somewhat different aspects of childhood depression [21]. Three studies of Kazdin and colleagues have investigated the correspondence between child and parent ratings in clinical populations [22-24]. All three studies found that parent and child ratings on the CDI were only slightly correlated (mean r = .09) and that children rated themselves lower than did their parents. In non-clinical samples, the reverse was found: mother CDI scores were significantly lower than child CDI scores. The relationship between Mother-CDI and CDI scores was modest (range between r = .37 and .61). Further analyses showed significant differences on two of the subscales, namely Affective Behavior and Interpersonal Relations [25].

The convergent validity of the CDI is good; CDI scores were highly associated with DSM-oriented symptoms of depression (r = .71) [16]. Results on the divergent validity are mixed. Often, a moderate to high association between the CDI ratings and anxiety ratings is found [16,26]. The discriminant validity of the CDI has been proven in multiple studies. The CDI differentiates between children with (clinical) depressive disorders and no disorder [27,28] and between depressed and non-depressed psychiatric youth [17,29]. However, there is also evidence that the CDI does not discriminate well between depressive disorders and other diagnoses [27,28]. Cut-off scores are useful to identify children at high risk for depressive problems. In the original CDI manual, a cut-off of 13 was recommended in a clinical sample (minimizing false negatives), and a cut-off of 19 was recommended in a nonclinical sample (minimizing false positives) [12]. Other studies have found that a CDI score of 16 has the best fit as a cut-off score for nonclinical samples [16,17]. Matthey and Petrovski [30] debate the use of these cut-off scores and conclude that the poor cut-off properties could account for the lack of difference in CDI ratings between depressive and other psychiatric disorders.

When investigating depression in children, demographic factors such as gender and age are important to consider. Most studies report that girls display more depressive symptoms than boys [5], and in clinically depressed adults, the gender ratio is 2:1 [31]. Also, studies on the CDI found higher scores for girls than boys [16]. However, some studies show contradictory results, namely, girls reporting lower [32] or similar scores compared to boys. One study only found gender effects on the subscale level of the original CDI using a different six-factor model for the subscales; girls had higher scores on dysphoria, social problems, self-deprecation, and biological dysregulation, while boys had higher scores on the externalizing subscale, controlling for age and other disorders [15]. Van Beek and Berg [33] found gender differences on the item level; items measuring crying and sadness were more characteristic of girls than boys.

Age could be moderating the gender effect. A so-called within-scale meta-analysis on mean CDI scores revealed that girls’ depression scores stayed stable from ages 8 to 11 and increased between ages 12 and 16. Boys’ CDI total scores were stable across ages 8 to 16. Girls’ CDI scores were somewhat lower until the age of 12, compared with boys (not significantly). At 13 years old, girls scored significantly higher than boys [34]. Similarly, girls’ depressive symptoms increased with age, while boys’ depressive symptoms stayed stable [16]. Overall, depressive symptoms increase after the age of 12 and peak around the age of 14 to 16 [35]. These differences plead for a thorough analysis of age and gender.

The CDI was adapted in order to extend symptomatic coverage and to renew norms by using a more representative standardization group. The improved CDI-2 contains 28 items and consists of two higher-order scales, namely emotional problems and functional problems, as well as four lower-order subscales, namely negative mood/physical symptoms, negative self-esteem, interpersonal problems, and ineffectiveness (Kovacs, 2011). The CDI-2 differs from the CDI in some aspects; two items were removed, three new items were added, and three items were rewritten. There is also a complementary parent version, which consists of 17 items. We translated the CDI-2 into Dutch and adjusted it so it could be used for 8 to 21-year-olds.

The psychometric properties of the American CDI-2 were examined and described in the CDI-2 manual [36]. Internal consistencies for both the total score (α = .91) and the subscales (ranging from α = .73 to α = .85) were high. The factor analysis showed the two higher-order scales and the four lower-order subscales. The parent-child agreement was weak to moderate (r = .34). The convergent validity was weak to moderate. The CDI-2 child version discriminated well between children with a major depressive disorder and matched controls, generalised anxiety disorder, CD/ODD, and ADHD [36]. On the child version, no differences between boys and girls were found. A significant age effect was found; 13 to 17-year-olds reported more depressive symptoms than 7 to 12-year-olds. Also, an age x gender interaction effect was found; boys’ scores stayed stable while girls’ scores increased with age. On the parent version, no age and gender effects were found. However, the CDI-2 has not been tested extensively in other languages so far.

The current study investigates the psychometric properties of the CDI-2 in a clinical and nonclinical Dutch population using both child and parent reports. Except for the CDI-2 manual, some psychometric properties of the CDI-2 have been investigated in other studies and in other populations, including Greek [37], Hispanic [38], Korean [39], Singaporean [40], and Tunisian [41] youth. However, the evidence remains limited, and no clinically depressed youth and parent reports were included. Also, more translations and norms are necessary so the CDI-2 can be used more effectively in depressed youth outside the United States [42]. Contrary to the American CDI-2, the Dutch CDI-2 has a wider age range and is age-appropriate for youth up to 21 years old. In this study, larger normative samples, a larger age range, the Dutch parent version, and mother and father reports were used compared to previous research. Furthermore, the factor structure was investigated separately in a sample of clinically depressed adolescents and adolescents from the general population and their parents.

The first goal was to replicate the promising findings of Kovacs [36] on the reliability of the CDI-2 and, more specifically, the internal consistency and the construct validity (factor analysis). Second, adding parents as an informant will enhance the reliability of the assessment, but the parent report is still expected to be moderately associated with the child report. Third, the validity of the CDI-2 was examined by means of the convergent validity and divergent validity. Fourth, the discriminant validity was investigated by comparing scores of children with a clinical depressive disorder, children with other psychiatric disorders, and children from the general population to identify children in need of treatment. Fifth, the criterion validity (cut-off scores) was determined by differentiating clinically depressed children from control children without a depressive disorder. Sixth, gender and age effects were analyzed.

Sample

A total of 2431 children and 2319 parents were included. The clinical sample consisted of 185 children and 216 parents and was obtained by combining three subsamples. One subsample was recruited at different youth mental health care institutions in the Netherlands as part of a randomized controlled trial investigating the effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) versus Care As Usual [43]. This subsample consisted of clinically depressed youth aged 12 to 21 years (n = 89) and their parents (n = 80). Children were included if they met the criteria of a depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder, if their age was between 12 and 21 years, and if they had an Intelligence Quotient ≥ 80. Children were excluded if they suffered from substance abuse, suicide attempts, psychosis, autism spectrum disorders, or had an untreated or primary diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Data from the two other clinical subsamples were gathered at two mental health care institutions as part of the diagnostic process. These children were seeking help for their mental health problems. The mean age of the clinical group was 15.4 years (SD = 3.4, range 8 to 21 years). The majority were girls (70.8%, n = 131). The primary diagnosis of these children were depressive disorder (47%, n = 87), ADHD (15.1%, n = 28), autism (9.7%, n = 18), dysthymic disorder (10.3%, n = 19), post traumatic stress disorder (4.3%, n = 8), generalized anxiety disorder (2.2%, n = 4), social phobia (2.2%, n = 4), obsessive-compulsive disorder (1.6%, n = 3), oppositional Defiant Disorder (1.6%, n = 3), depressive disorder not otherwise specified (1.1%, n = 2), specific phobia (0.5%, n = 1), panic disorder (0,5%, n = 1), separation anxiety disorder (0.5%, n = 1), anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (0.5%, n = 1) and other diagnoses (3.7%, n = 5). The clinical group was assessed in the clinic before they received treatment.

The control sample consisted of 2246 children and 2103 parents from the general population. This dataset consisted of four subsamples. One subsample (n = 688, 11 to 21 year olds) was recruited by master’s students in social sciences who were recruited via schools and were representative of the Dutch population based on gender, age, ethnicity, and educational level, comparable to the data from the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Two subsamples (n = 723 children, 8 to 12 year olds, and n = 1861 parents of youth aged 8 to 21) were recruited through external market research and the Area Health Authority. One sample (n = 835, 11 to 15 years old) was recruited as part of a prevention study for girls [44]. The mean age of the control children was 13.0 years old (SD = 3.2, range 8 to 21 years). The majority were girls (73.3%, n = 1647). Children and parents from the general population were tested in schools or at home. The control sample was comparable to the clinical group in terms of gender, χ2 = 0.55, p > .1, but not in terms of age, F(1, 2430) = 100.6, p < .01, indicating that the clinical group was older. All children and parents gave informed consent.

Measures

CDI-2: The Dutch version of the CDI-2 [45] is a 28-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the degree of depressive symptoms in children aged 8 to 21 years old. The CDI-2 is a revision of the 27-item CDI [12,46]. Respondents are asked to choose one out of three statements/descriptions that best fits how they have been feeling during the past two weeks, each description indicating the severity of the symptom; 0 (absence of symptom; e.g., I am sad once in a while), 1 (mild symptom; e.g., I am sad many times) and 2 (clear or severe symptom; e.g., I am sad all the time). The total score can be computed by summing up all items. Factor analysis by Kovacs [36] indicated that the CDI-2 consists of two higher-order scales and four lower-order scales. The higher-order scale emotional problems consists of two lower-order subscales: negative mood/physical symptoms (9 items) and negative self-esteem (6 items); the higher-order scale functional problems consists of the lower-order subscales ineffectiveness (8 items) and interpersonal problems (5 items).

The CDI-2 also has a complementary parent version. This parent version consists of 17 items (e.g., my child looks sad). Parents are asked to rate depressive symptoms of their child on a four-point scale ranging from (0) not at all to (3) much or most of the time. A total score can be obtained by summing up all the items. Also, the parent version consists of two higher-order scales, namely emotional problems (9 items) and functional problems (8 items).

The original American child and parent versions were translated and adapted to the Dutch language and setting. Subsequently, it was back-translated into English by two native speakers. We adjusted the CDI-2 in such a way that it is also suitable for young adults until the age of 21. Therefore, some items were slightly changed (e.g., work was added to school items).

KSADS: In the clinically depressed subsample, the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for school aged children, present and lifetime [47,48] child and parent versions were conducted to obtain diagnostic status. The KSADS is a widely used semi-structured diagnostic interview, which assesses a wide range of diagnoses (present and lifetime), including their severity. The views of the child, the parent, and the independent clinician are taken into account. Concurrent validity of the K-SADS-PL is supported. Also, the interrater agreement is high (range 93% to 100%) and test-retest reliability is excellent for present and lifetime diagnoses of major depression (.77 to 100) [47].

YSR/CBCL: To measure convergent and divergent validity, children’s problem behavior was assessed in children aged 8 to 21 by the Youth Self Report (YSR) [49,50] and in parents by the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) [51,52]. Both questionnaires contain two global syndrome scales, Internalizing problems and Externalizing problems, DSM scales, and problem scales. A high score indicates high psychopathology.

Statistical analysis

Missing data were extrapolated using the missing value analysis of SPSS (version 23). No more than 8% of the items were missing per questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency. To evaluate the model fit of the CDI-2 child and parent versions in both the community and clinical samples, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted in Mplus Version 7.4 [53]. Concerning the child version (28 items) of the community and clinical samples, a second-order CFA model was fitted to the data. This model included four lower-order latent subscales (i.e., ‘negative mood/physical symptoms’ [9 items]; ‘negative self-esteem’ [6 items]; ‘ineffectiveness’ [8 items]; and ‘interpersonal problems’ [5 items]), as well as two higher-order latent subscales, being ‘emotional problems’ on the one hand (including the lower-order latent subscales ‘negative mood/physical symptoms’ and ‘negative self-esteem’ [15 items]) and ‘functional problems’ on the other (consisting of the lower-order latent subscales ‘ineffectiveness’ and ‘interpersonal problems’ [13 items]). Further, concerning the parent version (17 items) of the community and clinical samples, a CFA model was fitted, including two latent subscales, being ‘emotional problems’ (9 items) and ‘functional problems’ (8 items). As items were rated on a three (child version) or four (parent version) point Likert scale, they were treated as categorical, and a WLSMV estimator was used to correct for non-normality [54].

Model fit was evaluated by means of various fit indices, more specifically the Root Mean Square of Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with values of ≤ .10 indicating an acceptable fit, values of ≤ .08 suggesting an approximate model fit, and values of ≤ .05 pointing to a good model fit [55], the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) as well as the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) with values of ≥ .90 indicating an adequate model fit [56], and the Weighted Root Mean square Residual (WRMR) with values of ≤ 1 suggesting a good model fit [56,57]. The latter, however, can be considered an experimental fit statistic and should not be given too much weight. As a matter of convention, the relative or normed chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio χ2/df) was also reported. However, this index is very sensitive to deviations from the conceptual model and is also highly affected by sample size [58]. Therefore, we did not use it to evaluate the model fit.

Parent-child agreement, convergent and divergent validity were calculated using Pearson correlations. Group differences on total CDI-2 scores were analyzed by means of analyses of (co)variance (ANCOVAs) to measure discriminant validity. Criterion validity was measured by establishing cut-off scores for the total and subscale scores of the CDI-2 child and parent versions using ROC curve analysis, as recommended by Matthey and Petrovski [30]. For the parent version, the combined scores of father and mother were employed. If only one parent participated, that score was used.

To test gender and age effects, ANOVAs were carried out. The partial η2 was used as an indicator of effect size. Age categories were divided into 8 to 12 year olds, 13 to 16 year olds, and 17 to 21 year olds based on developmental and psychological perspectives. At the age of 12, important developmental changes take place, such as cognitive development (from concrete operational to formal operational stage), physical changes (puberty development), and emotional changes [59,60]. Puberty usually lasts until the age of 16, as the physical-sexual maturation reaches its end phase. In the Netherlands, children above the age of 16 are considered adults according to the law. Therefore, children older than 16 were analyzed as a separate group in this study.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency coefficients were computed for the child and parent versions of the CDI-2. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the total score were .88 in the control group and .90 in the clinical group. For the higher-order subscales, Cronbach’s alphas were .82 (control sample) and .83 (clinical sample) for emotional problems and .75 (control sample) and .81 (clinical sample) for functional problems. The Cronbach’s alphas for the lower-order subscales were .70 and .70 for negative mood/physical symptoms, .72 and .81 for negative self-esteem, .70 and .75 for ineffectiveness, and .59 and .65 for Interpersonal problems, indicating a high degree of homogeneity on the total and higher-order subscales but moderate to insufficient consistency for the lower-order subscales.

The Cronbach’s alpha for the parent CDI-2 total score was .81 in the control group and .87 in the clinical group. Cronbach’s alpha for the subscale emotional problems was .77 in the control group and .85 in the clinical group, and for the subscale functional problems, .67 and .72.

Construct validity (confirmatory factor analysis)

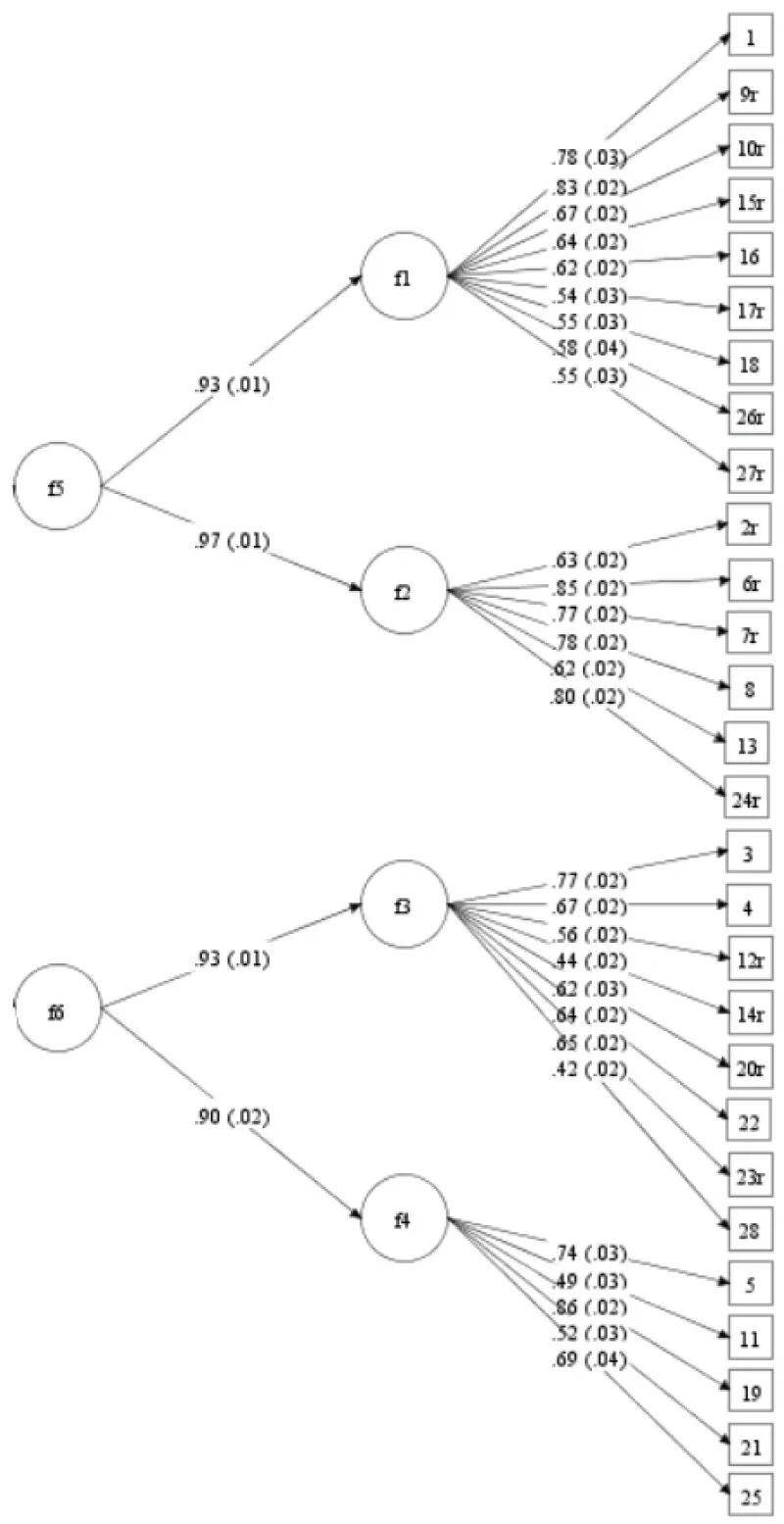

Concerning the child version in the control sample, the second-order CFA revealed very good fit indices (χ²/df = 4.14, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .95, TLI = .94). Except for the WRMR (1.62), but as this is an experimental fit statistic, it should not be given too much weight. Thus, this model had a very good fit to the data. Standardized factor loadings (all significant at the p < .001 level) and standard errors are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Second-order CFA of the self-reports of the control sample (n = 2246). f1 = Negative mood/physical symptoms; f2 = Negative self-esteem; f3 = Ineffectiveness; f4 = Interpersonal problems; f5 = Emotional problems; f6 = Functional problems.

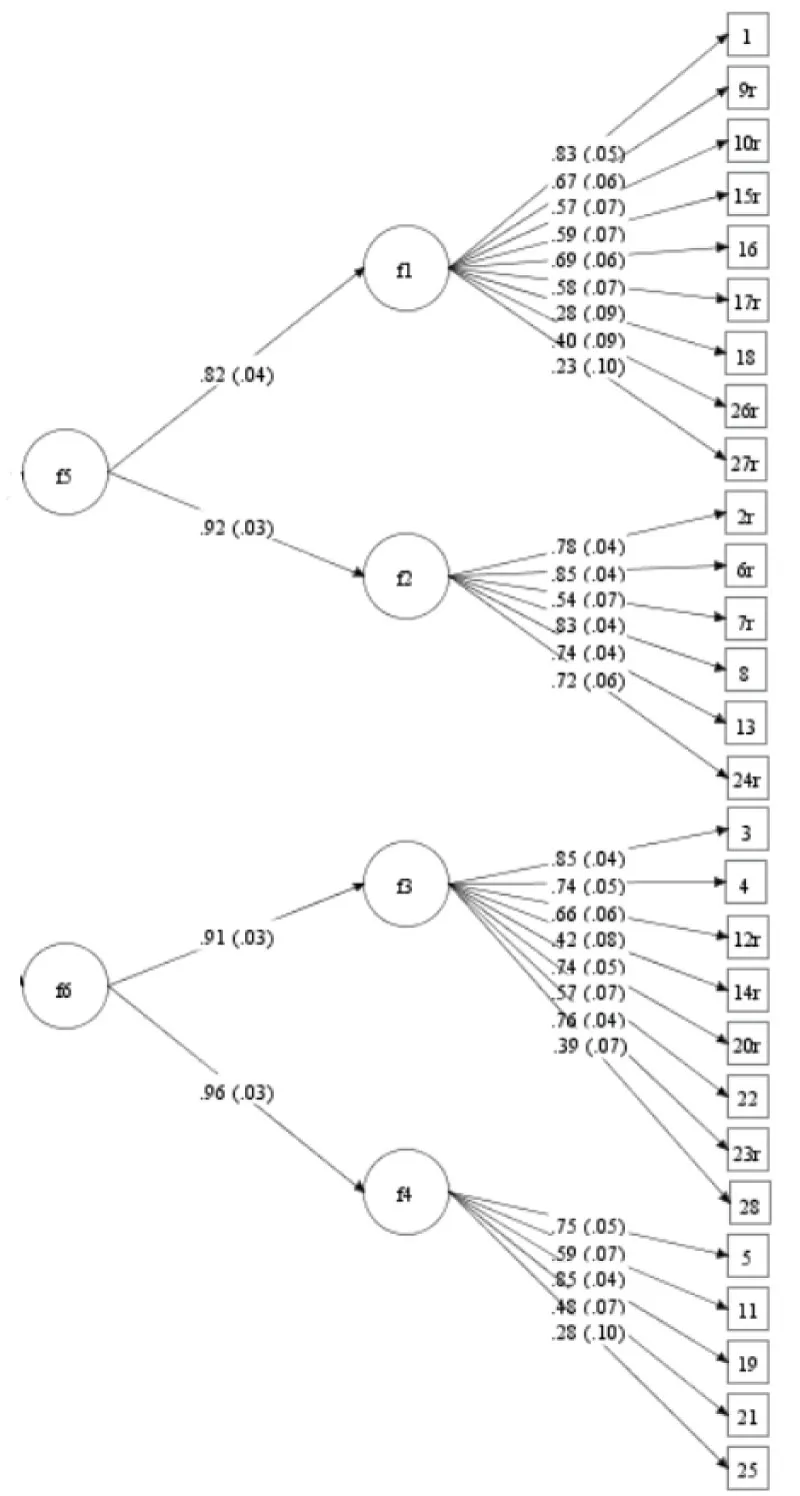

Concerning the CDI-2 child version in the clinical sample, the second-order CFA indicated very good model fit indices (χ²/df = 1.37, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .96, TLI = .96, WRMR = .94). Hence, this model showed a very good fit to the data. Standardized factor loadings (all significant at the p < .05 level) and standard errors are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Second-order CFA of the self-reports of the clinical sample (n = 185). f1 = Negative mood/physical symptoms; f2 = Negative self-esteem; f3 = Ineffectiveness; f4 = Interpersonal problems; f5 = Emotional problems; f6 = Functional problems.

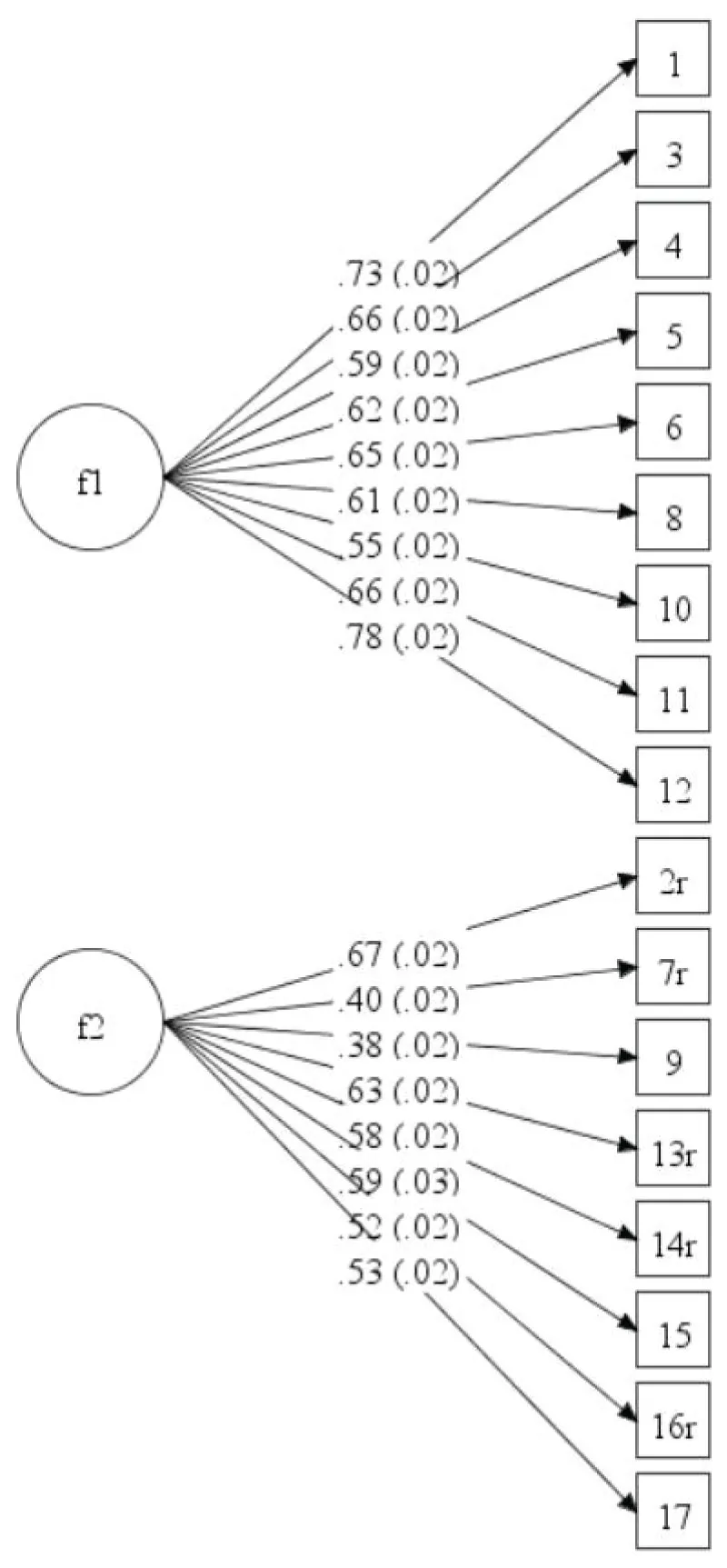

Concerning the parent version in the control sample, the CFA reflected unacceptable model fit indices (χ²/df = 20.31, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .83, TLI = .80, WRMR = 3.22) (note that we do not rely on χ²/df to evaluate the model fit). Standardized factor loadings (all significant at the p < .001 level) and standard errors are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: CFA of the parent reports of the control sample (n = 2103). f1 = Emotional problems; f2 = Functional problems.

Finally, concerning the parent version in the clinical sample, the CFA fit indices did not indicate a good model fit (χ²/df = 5.88, RMSEA = .15, CFI = .78, TLI = .75, WRMR = 1.78). Standardized factor loadings (all significant at the p < .001 level) and standard errors are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4: CFA of the parent reports of the clinical sample (n = 216). f1 = Emotional problems; f2 = Functional problems.

Parent-child agreement

In the control group, the parent-child agreement (n = 353) was moderate (r = .39). The parent-child agreement on the CDI-2 total score was higher in the clinical group (n = 215), namely r = .61, indicating a high agreement. In the control sample, the parent-child agreement between children and mothers (n = 133, r = .28) and fathers (n = 109, r = .27) was equal. In the clinical sample, children and mothers agreed slightly more (but not significantly) (n = 129, r = .67) than children and fathers (n = 74, r = .54), z = 1.39, p > 0.05.

Convergent and divergent validity

The convergent and divergent validity for the CDI-2 child version was moderate to good in the control sample. The CDI-2 total score was strongly correlated to higher and lower-order internalizing subscales of the YSR (r = .77 for internalizing, r = .62 for physical complaints, r = .66 for withdrawn and r = .72 for anxious/depressed) and moderately correlated to higher and lower-order externalizing subscales of the YSR (r = .52 for externalizing, r = .40 for rule breaking and r = .52 for aggressive). The convergent and divergent validity were good in the clinical sample. The CDI-2 total score was moderately correlated to the internalizing subscales of the YSR (r = .49 for internalizing, r = .47 for withdrawn and r = .46 for anxious/depressed) but not significantly correlated to physical complaints (r = .15) and not significantly correlated to the externalizing subscales of the YSR (r =. 18 for externalizing, r = .19 for rule breaking and r = .13 for aggressive).

The convergent and divergent validity for the CDI-2 parent version was only measured in the clinical sample. The CDI-2 parent total score is moderately correlated to the higher and lower-order internalizing subscales of the CBCL (r = .50 for internalizing, r = .30 for physical complaints, r = .47 for withdrawn and r = .49 for anxious/depressed) and non-significant to moderately correlated to the higher and lower-order externalizing subscales of the CBCL (r = .35 for externalizing, r = .16 for rule breaking and r = .41 for aggressive).

Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity of the CDI-2 child version was examined by comparing the total scores of clinically depressed children with those of children with other psychiatric disorders and control children by means of an ANCOVA with gender and age as covariates. Results indicated that clinically depressed children (M = 24.73, SD = 8.44) reported significantly more depressive symptoms than children with a diagnosis other than depression (M = 13.34, SD = 8.57) and control children (M = 7.44, SD = 6.33), F(2, 2429) = 349.50, p < .01, partial η2 = .25, see Table 1.

| Table 1: Mean CDI-2 child version scores and standard deviations in the control sample, the sample with other psychiatric disorders, and the clinically depressed sample. | ||||||||

| Control sample | Other psychiatric disorders | Clinically depressed | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F value | partial η2 | |

| N = 2246 | N = 74 | N = 111 | ||||||

| Total CDI-2 score | 7.44 | 6.33 | 13.34 | 8.57 | 24.73 | 8.44 | 349.50** | 0.25 |

| N = 1647 | N = 40 | N = 91 | ||||||

| Girls | 7.78 | 6.51 | 13.35 | 9.72 | 24.78 | 8.39 | 254.89** | 0.22 |

| N = 599 | N = 34 | N = 20 | ||||||

| Boys | 6.51 | 5.71 | 13.32 | 7.13 | 24.5 | 8.85 | 94.89** | 0.23 |

| N = 1245 | N = 31 | N = 3 | ||||||

| 8-12 year olds | 6.73 | 5.91 | 9.97 | 5.83 | 20.33 | 5.51 | 12.70** | 0.02 |

| N = 655 | N = 20 | N = 54 | ||||||

| 13-16 year olds | 9.09 | 7.09 | 12.8 | 9.54 | 25.35 | 9.17 | 124.41** | 0.26 |

| N = 346 | N = 23 | N = 54 | ||||||

| 17-21 year olds | 6.87 | 5.67 | 18.35 | 8.73 | 24.35 | 7.80 | 210.65** | 0.50 |

| Note. For all F values, p’s were < 0.01, partial η2 of .01-.05 = small effect size, .06-.13 = medium effect size, > .14 large effect size. | ||||||||

In line with these results, the parents of clinically depressed children also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms for their children (M = 23.60, SD = 7.52) than the parents of children with other psychiatric disorders (M = 16.87, SD = 7.78) and control children (M = 9.58, SD = 5.41), F(2, 2317) = 290.95, p < . 01, partial η2 = 0.20. This indicates that the discriminant validity is good, see Table 2.

| Table 2: Mean CDI-2 parent scores and standard deviations in the control sample, the sample with other psychiatric disorders, and the clinically depressed sample. | ||||||||

| Control sample | Other psychiatric disorders | Clinically depressed | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F value | partial η² | |

| N = 2130 | N = 112 | N = 104 | ||||||

| Total CDI-2 score | 9.88 | 5.41 | 16.87 | 7.78 | 23.60 | 7.52 | 290.95** | 0.20 |

| N = 1142 | N = 56 | N = 87 | ||||||

| Girls | 9.82 | 5.37 | 16.75 | 8.86 | 23.53 | 7.87 | 199.17** | 0.24 |

| N = 961 | N = 56 | N = 17 | ||||||

| Boys | 9.96 | 5.46 | 17.00 | 6.60 | 23.94 | 5.54 | 81.10** | 0.14 |

| N = 1526 | N = 57 | N = 4 | ||||||

| 8–12 year olds | 9.30 | 5.13 | 13.70 | 6.67 | 22.00 | 4.97 | 31.31** | 0.04 |

| N = 330 | N = 34 | N = 68 | ||||||

| 13–16 year olds | 11.64 | 5.96 | 20.38 | 8.60 | 24.25 | 7.62 | 122.74** | 0.37 |

| N = 247 | N = 21 | N = 32 | ||||||

| 17–21 year olds | 11.12 | 5.61 | 19.81 | 5.50 | 22.41 | 7.56 | 65.93** | 0.31 |

| Note. For all F values, p’s were < 0.01, partial η² of .01–.05 = small effect size, .06–.13 = medium effect size, > .14 large effect size. | ||||||||

Cut-off scores

Cut-off scores were established to differentiate between clinically depressed children and children without a depression diagnosis based on the CDI-2 total score. This cut-off score was obtained by determining the maximum sensitivity and specificity score of the CDI-2 for predicting any KSADS depressive disorder by means of ROC curve analysis. The opt cut-off score for the child version was 14. The sensitivity was 0.88, which indicates that 88% of the children who scored 14 or above the cut-off of 14 were identified by the CDI-2 as having a depressive disorder and really suffered from a clinical depressive disorder. There were 12% false negatives: clinically depressed children who were not identified as such by the CDI-2. The specificity of the CDI-2 child version was 0.84, which means that 84% of the children who scored below the cut-off were not identified by the CDI-2 as having a depressive disorder and indeed did not have a clinical depressive disorder. There were 16% false positives, children who were falsely identified as depressed by the CDI-2. For the parent version, the optimal cut-off score was 16. Sensitivity was 0.86, and specificity was 0.84.

Gender and age effects

In the control group, a significant gender effect was found; girls reported higher levels of depressive symptoms (M = 7.78, SD = 6.51) as compared to boys (M = 6.51, SD = 5.71), F(1, 2244) = 17.83, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.01. Also, a significant age effect was found; 13 to 16 year olds (M = 9.09, SD = 7.09) reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than 8 to 12 (M = 6.73, SD = 5.91) and 17 to 21 year olds (M = 6.87, SD = 5.67), F(2, 2243) = 32.34, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.03. Furthermore, a significant interaction effect between gender and age was found, F(5, 2240) = 15.84, p < .01, partial η2 = .03, indicating that 13 to 16-year-old girls reported the highest levels of depressive symptoms.

Parents in the control group reported no differences between boys and girls on the CDI-2 total score, F(1, 2101) = 0.31, p > .05. A significant age effect was found, F(2, 2100) = 33.75, p < .01, partial η2 = .03; parents reported higher levels of depressive symptoms in 13 to 16 year olds (M = 11.64, SD = 5.96) compared to parents of 8 to 12 (M = 9.30, SD = 5.13) and 17 to 21 year olds (M = 11.12, SD = 5.61). Furthermore, a significant interaction effect between gender and age was found, F(5, 2097) = 15.11, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.04, indicating that CDI-2 parent scores increased as the age of girls increased and that CDI-2 parent scores were the highest in 13 to 16-year-old boys.

In the clinical group, girls also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms (M = 21.29, SD = 10.25) as compared to boys (M = 17.46, SD = 9.45), F(1, 183) = 5.57, p = .02, partial η2 = 0.03. The CDI-2 total score increased when the child’s age increased; 8 to 12 (M = 10.88, SD = 6.46), 13 to 16 year olds (M = 21.96, SD = 10.78) and 17 to 21 year olds (M = 22.56, SD = 8.49), F(2,182) = 21.41, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.19. Again, a significant interaction effect between gender and age was found, F(5, 179) = 11.21, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.24, showing that CDI-2 total scores of boys increased with age, while the CDI-2 total score of the girls was at its peak in 13 to 16-year-olds.

Parents in the clinical group reported no significant differences between boys and girls on the CDI-2 total score, F(1, 214) = 3.58, p = .06. A significant age effect was found, F(2, 213) = 26.83, p < .01, partial η2 = .20; parents report higher levels of depressive symptoms in 13 to 16 year olds (M = 22.96, SD = 8.13) compared to parents of 8 to 12 (M = 14.25, SD = 6.86) and 17 to 21 year olds (M = 21.38, SD = 6.88). Furthermore, a significant interaction effect between gender and age was found, F(5, 210) = 12.87, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.24, showing increasing levels of depressive symptoms reported by parents with increasing age of boys and a peak of depressive symptom levels reported by parents in 13 to 16-year-old girls.

The current study examined the ability of the CDI-2 to detect and discriminate depressed children in a multi-group sample including clinically depressed children, children with other psychiatric disorders, control children, and their parents. The main results can be summarized as follows. First, the CDI-2 possesses good internal consistency for the total score, and the two higher-order factor structure does show a good fit for the child version but not for the parent version. Second, the parent-child agreement is moderate in the control group and high in the clinical group. Third, moderate to good convergent and divergent validity was found. Fourth, the CDI-2 total score differentiated between control children, children with other psychiatric disorders, and clinically depressed children based on child and parent report. Fifth, reliable cut-off scores were established. Sixth, gender differences were found for the child version but not for the parent version. Age differences were found for the child as well as the parent version.

Internal consistency and construct validity (confirmatory factor analysis)

The internal consistency of the CDI-2 child version was good for the total score and the higher-order scales and moderate for the lower-order subscales. The internal consistency of the CDI-2 parent version was good for the total score and the higher-order scales. The second-order CFA model (including two higher-order scales and four lower-order subscales) of the CDI-2 child version showed a good fit in both the control and clinical samples. The CFA model (including two higher-order scales) of the parent version of the CDI-2 showed an unacceptable fit. The factor analyses indicate that the subscales of the CDI-2 parent version are not reliable and do not reflect the same content as was proposed by Kovacs [36]. This is in line with studies examining the factor structure of the CDI, in which a variety of factor solutions (1 to 8) were found. It is also in line with a study also revealing different factor structures for the child and parent versions. This suggests that parents and children tend to focus on somewhat different aspects of childhood depression [18]. Therefor and in agreement with other authors [20], we propose to primarily use the CDI-2 child and parent total score as they are the most appropriate and reliable to use.

Parent-child agreement

The parent-child agreement was moderate in the control group and in line with previous research on depression [61] and psychopathology in general [62]. In general, there is a larger discrepancy between parent and child when reporting internalizing problems (.25) compared to externalizing problems (.30) [62]. Often, covert behaviors (thoughts and feelings) are not identified by parents, while overt behaviors (being tired, sadness) are. That is why children tend to overreport, and parents tend to underreport depressive symptoms [63]. It is also common in childhood and adolescence to display irritability as a symptom of depression rather than the more classic sadness symptoms, which makes it more difficult for the parents to identify depressive symptoms in youth, justifying the use of a self-report screening. It was concluded that if only the parent report were used, depression in the child might be missed [63]. However, using only a child report is not always indicated, as young children have a limited ability to verbalize their thoughts (e.g., on hopelessness) and their feelings, which makes it more difficult to detect signs of depressive symptoms by means of self-report. Although low parent-child agreement is often found [64], we can conclude that the parent-child agreement was good in the clinical group. This could be explained by the fact that the depressive symptoms are more severe and lead to more interference with daily life, making it more visible for the parents. In children with anxiety symptoms, the parent-child agreement on an anxiety questionnaire was also higher in the clinical sample compared to the nonclinical sample [65]. As was found in earlier research [66], parents reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than children. However, parental factors such as psychopathology (such as depression) can also influence parent-child agreement [67].

Convergent and divergent validity

The convergent and divergent validity for the CDI-2 child version was moderate to good in the control sample. The CDI-2 total score was strongly correlated to the internalizing subscales of the YSR and moderately correlated to the externalizing subscales of the YSR. The convergent and divergent validity were good in the clinical sample. The CDI-2 total score is moderately correlated to the internalizing subscales of the YSR (except for physical complaints) but not significantly correlated to the externalizing subscales of the YSR. The convergent and divergent validity for the CDI-2 parent version (only measured in the clinical sample) was also good. The CDI-2 parent total score was moderately correlated to the internalizing subscales and non-significantly to moderately correlated to the externalizing subscales of the CBCL. These results are in line with the findings of Kovacs [36].

The CDI-2 correlated highly with the anxiety/depressed subscales of the CBCL and the YSR. This can be explained by the high comorbidity between these two disorders. Some even argue that depression and anxiety can be seen as being on one single underlying common negative affect dimension [26,68]. In the control group, the moderate correlation with the externalizing scales of both the CBCL and the YSR is not surprising: the moderate relation between depression and behavioral problems can be explained by the fact that sometimes the adolescent displays irritability as a symptom of the depression. This can be falsely interpreted as behavioral problems. Indeed, research shows that behavioral problems are good markers of depressive symptoms [69].

Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity of the CDI-2 child version was good. Clinically depressed children reported significantly more depressive symptoms than children with other psychiatric disorders and control children. A large effect was found. In line with these results, the parents of clinically depressed children also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms for their children than the parents of children with other psychiatric disorders (other than depression) and control children. Also, a large effect was found. This is in line with previous research on the CDI [17,29].

Cut-off scores

Cut-off scores were established to identify children at risk of having a depressive disorder. The optimal cut-off score for the child version was 14 and 16 for the parent version. The Dutch cut-off score for the child version is comparable to the American cut-off score. The previous Dutch CDI cut-off score was 16 [46], but since the CDI-2 has different items, these two cannot be compared. Besides, the previous cut-off score was based on only 18 adolescents with a depressive disorder.

Gender and age effects

As expected from previous studies, girls in all groups reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than boys [5,16]. However, based on the parent version of the CDI-2, no gender differences were found.

Regarding age, in the control group, 13 to 16-year-olds reported higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to 8 to 12-year-olds and 17 to 21-year-olds. In the same way, parents in the control and clinical group also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms in 13 to 16-year-olds compared to parents of 8 to 12-year-olds and 17 to 21-year-olds. It seems that in our nonclinical group, the peak of reporting depressive symptoms is around puberty. In the clinical group, the CDI-2 total score (child version) increased with the child’s age. Previous studies are inconclusive, with cross-sectional studies showing no decrease in depression with the child’s age and longitudinal studies showing a decrease due to measurement effects [34]. In addition, prevalence rates of depression increase with age [70]. Besides, one study found that age was not related to original CDI ratings when controlling for confounding effects [15].

Gender could be a factor that could partially explain these findings. In the control and clinical group, 13 to 16-year-old girls reported the highest levels of depressive symptoms. A within-scale meta-analysis on mean CDI scores also revealed that girls’ depression scores stayed stable from ages 8 to 11 and increased between ages 12 and 16. The same study also found that 13-year-old girls scored significantly higher than boys [34]. In the control sample, parent scores increased as the age of girls increased, and CDI-2 parent scores were the highest in 13 to 16-year-old boys. In the clinical sample, the reverse was found; parent scores increased as the age of boys increased, while the CDI-2 parent total score was at its peak in 13 to 16-year-old girls. To explain the gender effect, theories regarding the physiological differences due to puberty, social differences, and more disclosure of feelings in girls have been proposed [71].

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. The first is the limited use of semi-structured interviews and the difference in classification of DSM-5 diagnoses. In the clinically depressed sample, the KSADS was assessed to obtain DSM-5 diagnoses. However, in the two other clinical subsamples, children were not assessed by means of a semi-structured interview, but their diagnoses were obtained through non-structured assessments and the therapist/psychiatrist’s clinical expertise and judgement. Second, there was a significant difference in mean age, indicating a higher mean age in the clinical group compared to the control group. However, the age range and gender distribution were similar.

Clinical and practical implications

The CDI-2 child and parent versions have good psychometric properties. Only the parent version did not show a good fit concerning the factor structure. Therefore, we suggest only using the total parent score. The CDI-2 can be used as a screening tool in both clinical and nonclinical samples, as a first step in the detection process of children and adolescents with depressive symptoms. According to the suggestions in previous manuals [36,46], we suggest assessing the CDI-2 two times (2 weeks apart) in order to reduce the false positives. Solely relying on the CDI-2 for diagnostic purposes is not recommended; interviews are necessary to establish a depressive disorder. A diagnostic interview remains the gold standard; the CDI-2 cannot determine a depressive diagnosis [72]. However, the CDI-2 can be easily used in a multiple-stage/method assessment strategy, in which the CDI-2 is used with a cut-off score. Apart from screening and diagnostic functionality, the CDI-2 can be used in prevention and intervention studies to assess treatment changes.

In conclusion, the Dutch version of the CDI-2 shows strong psychometric properties. This makes it a reliable tool for screening depressive symptoms in both clinical and non-clinical youth. The child self-report and parent versions work well for identifying at-risk individuals. However, the parent version has some structural issues, which means clinicians should focus on the total score instead of specific subscales. The findings also underscore the need for assessments from multiple sources, as parent-child agreement is moderate. Overall, the CDI-2 is a useful resource for early detection and diagnosis in Dutch mental healthcare. It helps ensure timely intervention for children and adolescents at different developmental stages.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate: The study design of the clinical sample was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Utrecht Medical Centre at Utrecht University, number 10/446. The study design of the control sample was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences of Utrecht University. All the study participants provided informed consent for their participation.

- Copeland WE, McGinnis E, Bai Y, Adams Z, Nardone H, Devadanam V, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(1):134-141.e2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

- Crockett MA, Martínez V, Jiménez-Molina Á. Subthreshold depression in adolescence: gender differences in prevalence, clinical features, and associated factors. J Affect Disord. 2020;272:269-276. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.111

- Wesselhoeft R, Sørensen MJ, Heiervang ER, Bilenberg N. Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):7-22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.010

- Carrellas NW, Biederman J, Uchida M. How prevalent and morbid are subthreshold manifestations of major depression in adolescents? A literature review. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:166-173. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.037

- Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CH. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):287-305. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12333

- Sigalas PD, Barkla X, McArdle P. Underdiagnosis of depression in young people. BMJ. 2014;348:g170. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g170

- Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379:1056-1067. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Smits N, Smit F. Screening and early psychological intervention for depression in schools: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:300-307. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-006-0537-4

- Siu AL, US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):360-366. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2957

- Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Laraque D, Stein RE, Glad-PC Steering Group, Sarvet B. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): part II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174082. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4082

- Beck A, Dryburgh N, Bennett A, Shaver N, Esmaeilisaraji L, Skidmore B, et al. Screening for depression in children and adolescents in primary care or non-mental health settings: a systematic review update. Syst Rev. 2024;13(1):48. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02447-3

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/book?vid=761e0bdc-c7a2-44a1-9730-c8aa4bed7424

- Bernaras E, Jaureguizar J, Garaigordobil M. Child and adolescent depression: a review of theories, evaluation instruments, prevention programs, and treatments. Front Psychol. 2019;10:543. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00543

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw B, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Cognitive_Therapy_of_Depression.html?id=L09cRS0xWj0C

- Gomez R, Vance A, Gomez A. Children’s Depression Inventory: invariance across children and adolescents with and without depressive disorders. Psychol Assess. 2012;24:1-10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024966

- Roelofs J, Braet C, Rood L, Timbremont B, van Vlierberghe L, Goossens L, et al. Norms and screening utility of the Dutch version of the Children’s Depression Inventory in clinical and nonclinical youth. Psychol Assess. 2010;22:866-877. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020593

- Timbremont B, Braet C, Dreesen L. Assessing depression in youth: relation between the Children’s Depression Inventory and a structured interview. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:149-157. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3301_14

- Huang C, Dong N. Dimensionality of the Children’s Depression Inventory: meta-analysis of pattern matrices. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23:1182-1192. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9779-1

- Jelínek M, Květon P, Burešová I, Klimusová H. Measuring depression in adolescence: evaluation of a hierarchical factor model of the Children’s Depression Inventory and measurement invariance across boys and girls. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249943. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249943

- Lee YS, Krishnan A, Park YS. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Inventory: an item response theory analysis across age in a nonclinical, longitudinal, adolescent sample. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2012;45(2):84-100. Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ956346

- Cole DA, Hoffman K, Tram JM, Maxwell SE. Structural differences in parent and child reports of children's symptoms of depression and anxiety. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):174-185. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.174

- Kazdin AE, Esveldt-Dawson K, Unis AS, Rancurello MD. Child and parent evaluations of depression and aggression in psychiatric inpatient children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1983;11(3):401-413. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00914248

- Kazdin AE, French NH, Unis AS. Child, mother, and father evaluations of depression in psychiatric inpatient children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1983;11:167-180. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00912083

- Kazdin AE, French NH, Unis AS, Esveldt-Dawson K, Sherick RB. Hopelessness, depression, and suicidal intent among psychiatrically disturbed inpatient children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(4):504-510. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.4.504

- Wierzbicki M. A parent form of the Children's Depression Inventory: reliability and validity in nonclinical populations. J Clin Psychol. 1987;43(4):390-397. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198707)43:4%3C390::aid-jclp2270430409%3E3.0.co;2-s

- Stark KD, Laurent J. Joint factor analysis of the children’s depression inventory and the revised children’s manifest anxiety scale. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:552-567. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3004_11

- Carey MR, Faulstich ME, Gresham FM, Ruggiero L, Enyart P. Children's Depression Inventory: construct and discriminant validity across clinical and nonreferred (control) populations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:755-761. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.5.755

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Spirito A, Bennett B. The Children’s Depression Inventory: a systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:955-967. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.52.6.955

- Hodges KK, Craighead WE. Relationships of the Children's Depression Inventory factors to diagnosed depression. Psychol Assess. 1990;2:489-492. Available from: https://awspntest.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1040-3590.2.4.489

- Matthey S, Petrovski P. The Children’s Depression Inventory: error in cutoff scores for screening purposes. Psychol Assess. 2002;14:146-149. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.2.146

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CI, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2002;492-509. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.492391

- Finch AJ, Saylor CF, Edwards GL. Children's Depression Inventory: sex and grade norms for normal children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(3):424-425. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.424

- van Beek Y, Berg A. Does less optimal nonverbal communication with peers predict the development of depression in adolescent boys and girls? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;1-11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00517-6

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the Children’s Depression Inventory: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:578-588. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.578

- Bertha EA, Balazs J. Subthreshold depression in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(10):589-603. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0411-0

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory, 2nd ed. Toronto (Canada): Multi-Health Systems; 2011. Available from: https://www.apa.org/obesity-guideline/depression-inventory.pdf

- Alexandrou G, Karanikola M, Chatzittofis A, Sokratous S. Reliability and validity of the full-length Greek-Cypriot version of the Children's Depression Inventory 2. Psychiatr Res Clin Pract. 2025. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.prcp.20250033

- Cumba-Avilés E. Systematic review on the use of the children’s depression inventory-2 among Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2020;42(2):191-214. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986320915170

- Cho Y, Lee EH, Hong SH, Joung YS, Kim JH. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of Children’s Depression Inventory 2 short version as a screening tool: a comparison with the standard 28-item version. Psychiatry Investig. 2022;19(1):54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2021.0296

- Anant N, Kaur D, Nadarajan R, Phua DY, Chong YS, Gluckman PD, et al. Validating the Children’s Depression Inventory-2: results from the growing up in Singapore towards healthy outcomes (GUSTO) study. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0286197. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286197

- Ayadi H, Boudabous J, Kerkeni A, Kraiem M, Yaich S, Moalla Y. Tunisian validation of the Children’s Depression Inventory-2 in school-based children. Curr Psychiatry Res Rev. 2025;21(3):389-399. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/0126660822272709231213062846

- Bae Y. Review of Children's Depression Inventory 2 (2nd ed.). J Psychoeduc Assess. 2012;30(3):304-308. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282911426407

- Stikkelbroek Y, Bodden DHM, et alHM, Dekovic M, van Baar AL. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in clinically depressed adolescents: individual CBT versus treatment as usual. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:314. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-314

- Rasing SP, Creemers DH, Janssens JM, Scholte RH. Effectiveness of depression and anxiety prevention in adolescents with high familial risk: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:316. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-316

- Bodden DHM, et al, Braet C, Stikkelbroek Y. CDI-2 questionnaire for depression in children and adolescents: manual. Amsterdam: Hogrefe Publishers B.V.; 2016. Available from: https://www.hogrefe.com/nl/shop/cdi-2-vragenlijst-voor-depressie-bij-kinderen-en-jongeren.html

- Timbremont B, Braet C. Handleiding Children’s Depression Inventory. Lisse: Swets Test Publishers; 2002. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/CDI.html?id=oR56zwEACAAJ

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980-988. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

- Reichart CG, Wals M, Hillegers M. Translation of K-SADS. Utrecht: HC Rümke Group; 2000.

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 profiles. Burlington (VT): Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1246863

- Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Koot HM. Handleiding voor de Youth Self-Report (YSR). Rotterdam: Sophia Kinderziekenhuis, Erasmus MC; 1997. Available from: https://pure.eur.nl/en/publications/handleiding-voor-de-youth-self-report-ysr/

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profiles. Burlington (VT): Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=79550

- Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Koot HM. Manual for the CBCL/4-18. Rotterdam: Sophia Children's Hospital, Erasmus MC; 1996. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1709339

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles (CA): Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2253227

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An evaluation of alternative methods for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol Methods. 2004;9:466-491. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466

- Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(4):462-494. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108314720

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: concepts, issues and applications. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1995;76-99. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1015696

- Yu CY. Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes [doctoral dissertation]. Los Angeles (CA): University of California; 2002. Available from: https://www.statmodel.com/download/Yudissertation.pdf

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. Available from: https://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files4/befc0f8521c770249dd18726a917cf90.pdf

- Mul D. Puberteitsontwikkeling van Nederlandse kinderen. Tijdschr Seksuologie. 2004;28:82-86. Available from: https://www.tijdschriftvoorseksuologie.nl/images/content/pdfs/2004-28-2%20Puberteitsontwikkeling%20van%20Nederlandse%20kinderen.pdf

- Weiss B, Weisz JR, Politano M, Carey M, Nelson WM, Finch AJ. Developmental differences in the factor structure of the Children's Depression Inventory. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:38-45. Available from: https://weiszlab.fas.harvard.edu/sites/g/files/omnuum9551/files/jweisz/files/weiss_weisz_politano_et_al_1991_a_journal_of_cons_and_clinc_psych.pdf

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:483-509. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DAG, Burgers DE, Rabinowitz J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(4):858-900. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0038498

- Pavuluri M, Birmaher B. A practical guide to using ratings of depression and anxiety in child psychiatric practice. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:108-116. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-004-0050-8

- Bivins EJ, Buckland EK, Pinciotti CM, Riddle DB. Parent-child agreement on depressive symptoms in depressed and suicidal youth. J Child Fam Stud. 2025;34:2358-2368. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-025-03159-z

- Muris P, Bodden DHM, et al, Hale W, Birmaher B, Mayer B. SCARED-NL. Vragenlijst over angst en bang-zijn bij kinderen en adolescenten. Handleiding bij de gereviseerde Nederlandse versie van de Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. Amsterdam: Boom Test Uitgevers; 2007. Available from: https://pure.eur.nl/en/publications/scared-nl-vragenlijst-over-angst-en-bang-zijn-bij-kinderen-en-ado/

- King CA, Katz SH, Ghaziuddin N, Brand E, Hill E, McGovern L. Diagnosis and assessment of depression and suicidality using the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-2.3). J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25:173-181. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025739730823

- Löchner J, Hämmerle S, Ghezih S, Starman-Wöhrle K, Schulte-Körne G, Platt B. Parent-child agreement on children's psychopathology and the impact of parental depression. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2023;33(1):e1993. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1993

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:316-336. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316

- Boots DP, Wareham J, Weir H. Gendered perspectives on depression and antisocial behaviors: an extension of the failure model in adolescents. Crim Justice Behav. 2011;38:63-84. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810388504

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:809-818. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006

- Breslau J, Gilman SE, Stein BD, Ruder T, Gmelin T, Miller E. Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(5):e1139. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.105

- Fristad MA, Emery BL, Beck SJ. Use and abuse of the Children’s Depression Inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:699-702. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.699