More Information

Submitted: 20 February 2020 | Approved: 07 March 2020 | Published: 09 March 2020

How to cite this article: Ratanasiripong P, Tsai S. Impact of Christian meditation and biofeedback on the mental health of graduate students in seminary: A pilot study. Insights Depress Anxiety. 2020; 4: 019-024.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ida.1001015

ORCiD: orcid.org/0000-0002-9179-1615

Copyright License: © 2020 Ratanasiripong P, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Impact of Christian meditation and biofeedback on the mental health of graduate students in seminary: A pilot study

Paul Ratanasiripong* and Sun Tsai

California State University, Long Beach, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Paul Ratanasiripong, California State University, Long Beach, USA, Tel: +(562) 985‐2534; Email: [email protected]

With increasing awareness of the mental health issues among the clergy and seminary students, it is important to explore possible interventions to help address their mental health concerns. This pilot study examined the impact of Christian meditation and biofeedback on levels of stress, anxiety, and depression of seminary students. Participants of this study included 20 theology students from two seminary campuses. Participants were of various ethnic backgrounds and had an average age of 31. At the beginning of the study, participants were randomly assigned to practice either Christian meditation or biofeedback for 4 weeks, three times per day, and to keep a log of their practice times. The results from the paired samples t-tests indicated that both Christian meditation and biofeedback significantly reduced the levels of stress, anxiety, and depression experienced by the participants. ANCOVA indicated that neither intervention was more effective than the other. Seminaries, churches, and pastoral care groups should look into these interventions as a good source to help their clergy cope with stress, anxiety and depression.

Clergy have been one of the oldest helping professions when it comes to emotional, spiritual, and personal conflict. As with any helping profession, it can be a difficult job. The role of clergy can take on many roles and can lead to many mental health issues such as stress, anxiety, and depression. One the one hand, ministry in the church can be a very rewarding experience; but, on the other, it can be overwhelming. In the gospel of Mark, Jesus asks his disciples to come away to a quiet place and get some rest, because they were helping so many people that they did not even get a chance to eat (Mark 6:30-31, New International Version). Jesus knew the importance of rest for the clergy because it can be a demanding and burdensome work. Many who have experienced working in the church, specifically as clergymen and clergywomen, can deeply empathize with Jesus’s twelve disciples. Helping others in the role of clergy can lead even the strongest of leaders to work themselves too hard, leading to symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression.

Stressors for clergy seem to come from all directions. Four critical stressors are personal criticism, boundary ambiguity, presumptive expectations, and family criticism [1]. McMinn, et al. [2], describe that the occupational stress of an average clergyman or woman can be great and these stressors can range from financial hardships to self-image issues. Clergy seem to deal with a broad range of difficulties in their line of work, yet, there does not seem to be many available resources for them. This may come from the false, but pervasive assumption that clergy have transcendent behaviors, thoughts, and emotions [3]. Another significant finding stated that the primary form of care for clergy was self-care or, in other words, intrapersonal coping [4]. Many clergy prefer to deal with their problems alone by engaging in spiritual disciplines or in taking time off from church work. These findings fall in line with the idea that many clergy feel uncomfortable with reaching out to others and asking for help.

Seminary students also face the same issues that clergy face, and at the same time they have to deal with the stressor of attending graduate school. Furthermore, not a lot of research has been done on interventions for the stress seminary students face while in school and in ministry. This population faces a unique set of stressors that do not quite fit in with an average graduate student or an established clergyperson. They are usually both practicing in ministry while facing the demands of being in school. According to Miner [5], this stress is especially high for those who are leading ministry solo since they do not have the benefit of working within a team. In short, a seminary student is often dealing with multiple areas of stress as both a higher education student as well as a member of the clergy. The unique stressors they face while in the beginning years of their ministry is all the more reason why their mental health and possible interventions for these issues should be examined.

The purpose of this pilot study was to help fill in a gap in research when it comes to clergy. There is a dearth of research when it comes to helping find methods of coping for this population. More specifically, the purpose of this study is to compare two interventions, one based in psychology and one based in Christian spirituality, to see if one is more effective than the other in improving the mental health of seminary students. This study compares and contrasts the interventions of Christian meditation and biofeedback. Christian meditation is the practice of focusing on the scriptures, on the person of God, and/or on loving the self and others for the purpose of spiritual growth and/or personal healing [6]. Biofeedback is the use of a device to become aware of psychological functioning so that a person can become aware of and positively change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviors [7]. First, this study would examine if Christian meditation or biofeedback has any effect on stress, anxiety, and depression. Secondly, this study would test whether or not there are significant differences between employing Christian meditation or biofeedback in the reduction of stress, anxiety, and depression. In addition, this pilot study was conducted to assess feasibility. As with most populations, this group has its own unique set of traits that may or may not be advantageous to researchers. This study explores what possible roadblocks or unknown avenues would arise when working with seminary students.

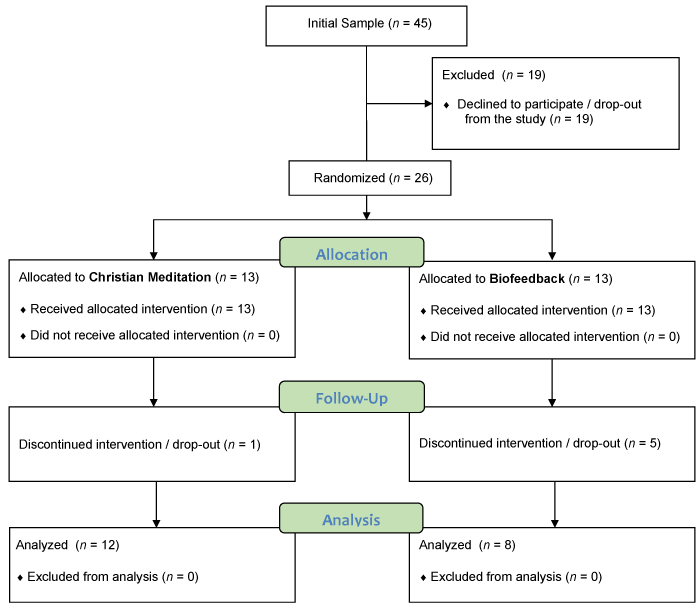

Participants

For this pilot study, only seminary graduate students who were completing a degree in theology were eligible to participate. All participants were enrolled in 1 of 2 seminaries in the United States and working or volunteering at a church or parachurch ministry either full-time or part-time. The participants were recruited from classrooms and through posted flyers. They were informed that their participation was on a voluntary basis and they could withdraw from the study at any time. Individuals who did not complete both the pre- and post-test questionnaires were omitted from the study. Originally, 45 people signed up for the study, but 19 people dropped out before beginning the study due to time constraints. Over the course of the 4-week study, 6 people were not able to complete the study. In total, there were 20 participants who completed the study, with 12 in the Christian meditation group and 8 in the biofeedback intervention group. The average age of participants was 31 (range = 23-61). The participants were identified as Asian/Pacific Islander (5), Latino/Hispanic (1), European American (13), and multiracial (1). 8 of the participants were married, 11 were single, and 1 was separated (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the study.

Procedure

After the participants were recruited, they were randomly assigned to either the Christian meditation group or the biofeedback group. Each group had a 60-minute pre-intervention meeting. At each meeting, participants filled out an informed consent, the pre-intervention questionnaires, and were trained to use their biofeedback device or the Christian meditation guidelines. For the next four weeks, the participants logged their progress. They were asked to document the number of minutes they spent practicing their device or meditating. Both groups were asked to practice their intervention three times a day – morning, midday, and before bed. At the end of four weeks all the participants met again for the post-intervention questionnaires and collection of practice logs.

Christian meditation

Christian meditation has a very specific focus which is for humans to communicate with God [8]. Christian mediation usually involves incorporating the Bible, or Scripture, as a vehicle through which Christians can hear the voice of God [8]. Christian meditation, like other forms of meditation, also emphasizes on becoming focused, nonjudgmental, and centering oneself. However, Christians see the growth of their faith as being highly collaborative with God [8], thus, the goal of this type of mediation is not to become blank or transcend reality, but to sit, rest in, and connect with God.

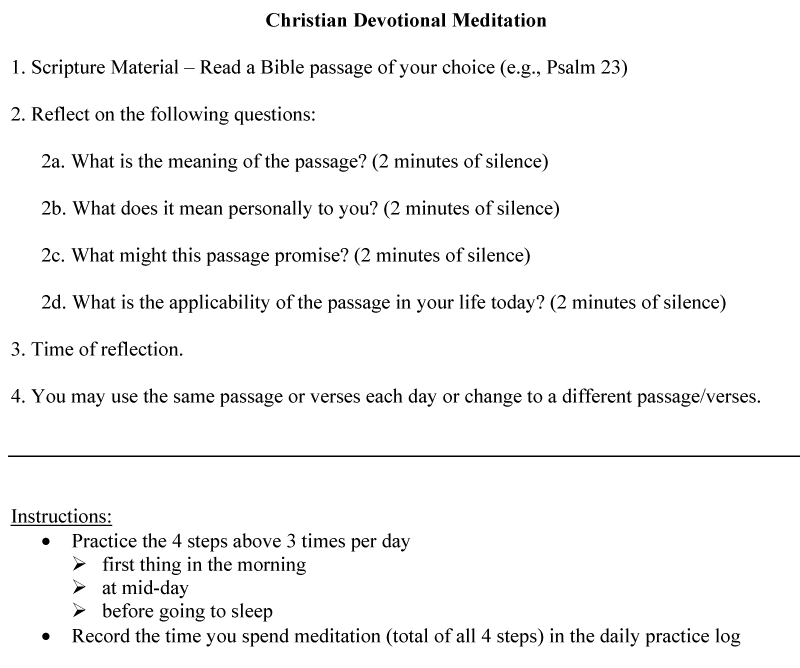

The training for the Christian meditation occurred in a group setting after the initial questionnaires measuring stress, anxiety and depression levels were taken. The Christian meditation training began with a brief introduction on Christian meditation and its various forms. Participants were asked if they were familiar with different methods of Christian meditation and they were asked to share with the group. Next, the participants were given a Christian Devotional Meditation guide as adapted from a study by Carlson, Bacaseta, and Simanton [9] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Christian devotional meditation guide.

The researcher went step-by-step through each section of the guide and clarified any questions. The first step was to help each participant come up with examples of verses or books of the Bible that they would like to meditate on. By helping participants brainstorm ideas on how to start the meditation process the researcher was hoping it would avoid any unnecessary lag time before the subjects could begin practicing their Christian meditation. If the participants did not have any ideas, suggestions were given by other participants. Next, the researcher went through the second step which would be to spend two minutes on the meaning of the passage, two minutes on what it personally meant to them, two minutes on what this passage might promise, and two minutes on the applicability of the passage in their life. The last step was to have another two minutes of listening and reflection in silence. Once the Christian Devotional Meditation was fully explained to the participants, the researcher went over the progress log and how to keep track of the meditation times (Figure 2).

Biofeedback intervention

This technique employs a hand-held device that one could easily carry around to monitor physiological reactions in order to positively modify thoughts, feelings or behaviors. This is done by monitoring heart rate variability (HRV). The training for HRV begins with the individual becoming aware of their involuntary HRV. Next they learn to breathe slowly while thinking and feeling positive emotions. Through the breathing and focusing on positive emotions, the individual learns how to control their HRV and the end result could be a reduction in stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [7].

The training for the biofeedback was given after administering the initial survey. The training began with a brief introduction on the way bodies physically manifest stress. The researcher explained that the biofeedback device measures heart rate variability and that it trains the user to breathe deeply which can lead to the relaxation of the body. In addition to the breathing, the participants were trained to focus on appreciative thoughts. In order to accomplish this, the researcher encouraged participants to focus on the heart and specifically three areas: heart focus, heart breathing, and heart appreciation. Heart focus was remembering that biofeedback is about monitoring the heart and how it is essential to our lives. Next, the heart breathing, is to remember that oxygen is life-giving and that it replenishes our heart. Lastly, heart appreciation is to think of appreciative thoughts while breathing deeply. These thoughts could be imagining a beautiful sunset or other nature scenes, holding a pet, or being with a loved one.

Next the researcher trained participants on how to use the portable biofeedback device which included: on/off button, volume, brightness, indicator bar, top and bottom indicator lights, and the restart function. The participants spent some time getting familiar with the device. Once the participants were comfortable with it, they were asked to use the device in the presence of the researcher to get one full indicator bar. Once that was done, the researcher went over how to log their progress including when and how to document the time.

Instruments

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): The PSS measures the level of stress perceived by the individual within the past month [10]. This was used to determine the level of stress of the participant before the intervention and after the intervention. The PSS has 10 items on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = very often) and a higher score indicates a higher level of perceived stress. Previous biofeedback study using the PSS had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 [11]. Another online intervention study had a Cronbach alphas for the PSS between 0.86 and 0.88 [12]. For the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the PSS is 0.83.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): Anxiety levels in the study were measured by the STAI-Trait version [13]. STAI was used to gather information on the current anxiety levels of the participants before the intervention was implemented and after the intervention was completed. STAI has 20 items with a 4-point Likert scale with 0 = not at all and 3 = very much so. The STAI has been shown to have good reliability among North American populations [14]. In another study, the Cronbach’s alpha for STAI was 0.88 [15]. This current study’s Cronbach’s alpha for the STAI is 0.91.

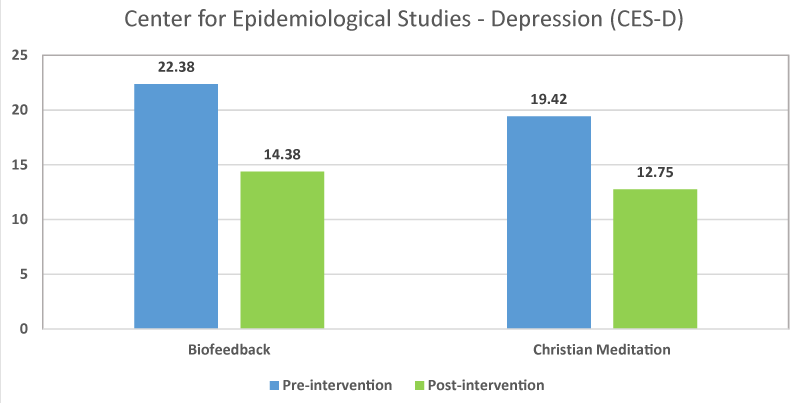

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D): Depression levels of the participants were measured by CES-D [16] both before the intervention and after the intervention. This scale has 20 items on a 4-point Likert scale with 0 = rarely or none of the time and 3 = most or all of the time. A higher score on the CES-D indicates higher levels of depression. Previous biofeedback study using the STAI had a Cronbach’s alpha between 0.87 and 0.89 [7]. Another study that investigated the level of depression of graduate students using the CES-D found that the reliability for the sample was 0.93 [17]. For the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D is 0.90.

Biofeedback results

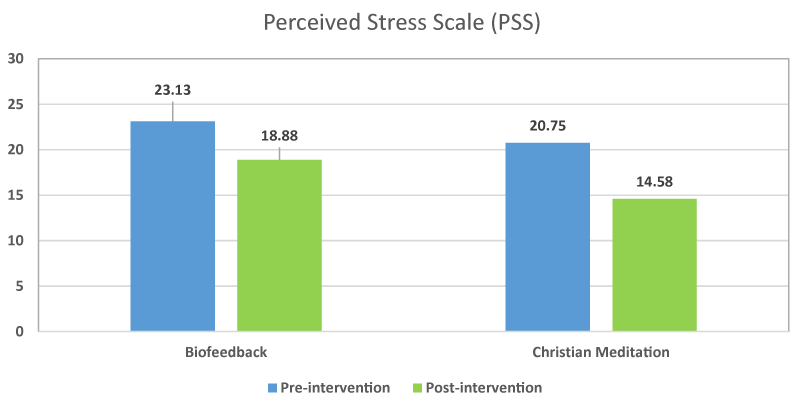

Paired samples t-test showed that there was a significant difference in scores for the PSS pretest (M = 23.13, SD = 3.31) and the PSS posttest (M = 18.88, SD = 6.56), t (7) = 2.71, p < 0.05. This result suggests that the perceived stress of the participants significantly decreased after they used the biofeedback intervention.

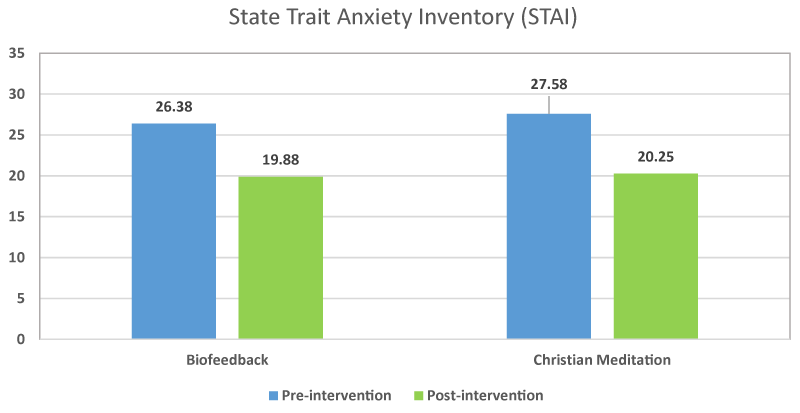

Paired samples t-test also showed that there was a significant difference in scores for the STAI pretest (M = 26.38, SD = 5.73) and the STAI posttest (M = 19.88, SD = 7.02), t (7) = 2.49, p < 0.05. The result suggests that there was a significant decreased in the state anxiety level of the participants after using biofeedback intervention.

Additionally, paired samples t-test showed that there was a significant difference in scores for the CES-D pretest (M = 22.38, SD = 6.74) and the CES-D posttest (M = 14.38, SD = 6.55), t (7) = 3.59, p < 0.01. This result suggests that the depression level of the participants decreased significantly after using the biofeedback intervention.

Christian meditation results

Paired samples t-test showed that there was a significant difference in scores for the PSS pretest (M = 20.75, SD = 6.78) and for the PSS posttest (M = 14.38, SD = 5.14), t (11) = 4.62, p < 0.01. This result suggests that the perceived stress of the participants decreased significantly after using Christian meditation.

Paired samples t-test also showed that there was a significant difference in scores for the STAI pretest (M = 27.58, SD = 12.18) and the for the STAI posttest (M = 20.25, SD = 11.96), t (11) = 3.04, p < 0.05. This result suggests that there was a significant decreased in anxiety of the participants after using Christian meditation.

Lastly, paired samples t-test showed that there was a significant difference in scores for the CES-D pretest (M = 19.42, SD = 12.15) and the CES-D posttest (M = 12.75, SD = 9.11), t (11) = 3.60, p < 0.01. This result suggests that the levels of depression of the participants decreased significantly after using Christian meditation.

Christian meditation verses biofeedback

ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) showed that for the PSS (F = 0.17, p = 0.69), there was no significant difference between the Christian meditation group and Biofeedback group. ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) also showed that for the STAI (F = 0.04, p = 0.84), there was no significant difference between the Christian meditation group and Biofeedback group. Additionally, ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) showed that for the CES-D (F = 0.04, p = 0.85), there was no significant difference between the Christian meditation group and Biofeedback group. These ANCOVA results suggest that while both interventions were effective in decreasing the overall perceived stress, anxiety, and depression of the participants, one intervention was not found to be more effective than the other (Figures 3-5).

Figure 3: Pre- and Post-Intervention Scores for Perceived Stress Scale.

Figure 4: Pre- and Post-Intervention Scores for State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Figure 5: Pre- and Post-Intervention Scores for CES-D.

The results of this pilot study indicate that both biofeedback and Christian meditation helped to significantly decrease the levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in seminary students who participated in this study. Between the two interventions, the data did not show any significance as to whether one method was more effective than the other. Thus, both interventions seemed to help this population with their stress, anxiety, and depression.

Biofeedback and Christian meditation both employ the technique of staying in the present moment rather than dwelling on the past or the present. Also, they both employed some type of positive thinking. For biofeedback, clients were encouraged to think appreciative thoughts along with their breathing. For Christian meditation, connecting with God and hearing his voice through prayer and scripture can be very positive and uplifting. Thus, staying in the moment and positivity were two commonalities that these interventions had and that may have attributed to their success in reducing stress, anxiety and depression.

As prior studies on clergy have suggested, this population needs better coping mechanisms [5,18,19]. The results of this study suggest that both Christian mediation and biofeedback offer a viable method to help clergy handle the stresses that come from many different directions. This study suggests that clergy can respond well when low-cost and time effective interventions are used. Results indicate that Christian mediation and biofeedback have positively impacted the mental health of seminary students. Thus, seminaries, churches, and pastoral care groups should look into these interventions as a good source to help their clergy cope with stress, anxiety and depression.

This study has looked into a population that is underserved, but the needs are great [18]. Even in conducting this study, it was made clear to the researcher that this population is overworked and overstretched by the demands of work, school, and family. From the 45 individuals who signed up to participate only 26 were able to make the trainings and six more dropped out through the course of the four week period. The reasons from the drop outs ranged from forgetting to practice the interventions to not having enough time to attend trainings. This adds to the growing evidence that this population needs better coping skills. The implications of this study for seminary schools may be that their students are in dire need of interventions and education about the stresses and demands that come with entering this profession. Another implication for seminary schools is that helping create a culture in which seeking help is not only encouraged but expected would help their students receive the assistance they need.

In addition, those who participated in the study benefitted from the experience which shows how primed this group is to receiving help. Further research can expound upon the findings of this study. Furthermore, both spiritual and psychological interventions seemed to have a positive impact on the mental health of seminary students. This study employed non-evasive and low-cost methods, but it would be interesting to see in further studies if other types of interventions may also make an impact. These might include support groups, in class interventions, or school-wide education about the needs of those in seminary. Another interesting finding from the previous research is that clergy prefer more intrapersonal forms of coping [2] and this is the type of interventions used in this research study. Since this is a pilot study with small sample size, a control group was not established. Future study that includes a control group could give more information on the impact of these interventions as well as explore other factors that may have led to this current study’s findings.

This research implicates that there is a need for churches to become aware of the issues their clergy face. As many previous studies have indicated [5,18,19], clergy are in roles that often blend into their family life as well as personal lives. According to Beebe [18], many clergy do not have a healthy differentiation between their self and their roles as clergy. If left unchecked, clergy who do not know how to differentiate between work demands and personal life demands will eventually burnout [18]. However, alongside this knowledge that clergy tend to have poor boundaries between work and home, there is an implicit expectation among churches that the weaknesses of the clergy be hidden from their congregation [20]. These high and unreachable expectations, along with the diversity of roles and demands, creates a very high stress environment. One concrete implication of this study for churches may be that their clergy may respond well to the two interventions used in this study. Perhaps congregations may create a space or even allow time for their clergy to participate in these types of interventions during certain times of the year as a required part of their ministry. Once again, similar to the implications for seminaries, churches may want to invest in creating a culture change in which clergy are not just encouraged to seek help, but are expected to seek it.

Implications for therapists would be that this population experience stress, anxiety and depression, and could use therapeutic help. Yet, because of the stigma of showing weaknesses or failures combined with the intrapersonal coping tendencies of this group, they may not willingly come into receive therapeutic help. Thus, normalizing therapy and advocating support for this population would be needed both among clergy and church congregations. Also, cultural awareness while treating clergy will be very important. There may be a strong sense of failure, guilt, or defensiveness among the clergy as a result of false expectations on how to deal with the problems that arise. On the other hand, based on this study, this group may highly benefit from therapeutic interventions. This is evidenced by the fact that the interventions in this study reduced stress, anxiety, and depression levels the participants. Moreover, since this population is also part of the helping profession, they may be more open to help once they receive it. A final implication for therapists is that psychoeducation for clergy will be very important. Helping clergy understand that their struggles are not abnormal and to validate the pressures that they face in being a religious leader may be crucial to helping them feel at ease in the therapeutic setting.

- Lee C, Iverson-Gilbert J. Demand, support, and perception in family-related stress among Protestant clergy. Fam Relat. 2003; 52: 249-257.

- McMinn MR, Lish RA, Trice PD, Root AM, Gilbert N, et al. Care for pastors: Learning from clergy and their spouses. Pastoral Psychol. 2005; 53: 563-581.

- Proeschold-Bell RJ, Miles A, Toth M, Adams C, Smith BW, et al. Using effortreward imbalance theory to understand high rates of depression and anxiety among clergy. J Prim Prev. 2013; 34: 439-453. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23975208

- Meek KR, McMinn MR, Brower CM, Burnett TD, McRay BW, et al. Maintaining personal resiliency: Lessons learned from evangelical protestant clergy. J Psychol Theol. 2003; 31: 339-347.

- Miner MH. Burnout in the first year of ministry: Personality and belief style as important predictors. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2007; 10: 17-29.

- Garzon F. Mindfulness and Christian devotional meditation. 2011.

- Ratanasiripong P, Kaewboonchoo O, Ratanasiripong N, Hanklang S, Chumchai P. Biofeedback intervention for stress, anxiety, and depression among graduate students in public health nursing. Nurs Res Pract. 2015; 2015: 160746. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25954515

- Blanton PG. The use of Christian meditation with religious couples: A collaborative language systems perspective. J Fam Psychother. 2002; 13: 291-307.

- Carlson R, Bacaseta PE, Simanton, DA. A controlled evaluation of devotional meditation and progressive relaxation. J Psychol Theol. 1988; 16: 362-368.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24: 385-396. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6668417

- Ratanasiripong P, Ratanasiripong N, Kathalae D. Biofeedback intervention for stress and anxiety among nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. IRSN Nurs. 2012; 2012: 827972. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22811932

- Hintz S, Frazier PA, Meredith L. Evaluating an online stress management intervention for college students. J Couns Psychol. 2015; 62: 137-147. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24635586

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. 1983.

- Maynard DB, Campbell MH, Devonish D, Leon T, Emmanuel MK, et al. Psychometric properties and factorial structure of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait version (STAI-T) in Caribbean university students. J Psychol Afr. 2010; 20: 7-12.

- Campbell MH, Roberti JW, Maynard D, Emmanuel MK. Factorial structure of depressive symptoms in an Anglophone Caribbean university student population: Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory-II. Interam J Psychol. 2009; 43: 577-585.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977; 1: 385-401.

- Peluso DL, Carleton RN, Asmundson GG. Depression symptoms in Canadian psychology graduate students: Do research productivity, funding, and the academic advisory relationship play a role? Can J Behav Sci. 2011; 43: 119-127.

- Beebe RS. Predicting burnout, conflict management style, and turnover among clergy. J Career Assessment. 2007; 15: 257-275.

- Randall KJ. Clergy burnout: Two different measures. Pastoral Psychol. 2013; 62: 333-341.

- Cappa P. Crisis intervention for clergy. J Psychol Christian. 2005; 24: 263-265.